There are dozens of ingredients that influence our surface weather conditions. One of the strongest influences comes from water vapor. The main ways we tend to note water vapor near the surface are via measurements of Relative Humidity (RH), Dew Point Temperature (DP), and Precipitable Water (PWAT). You may have noticed you often hear us say things like “this dry air will allow temperatures to (warm/cool) quickly,” or “high precipitable water values could lead to torrential rain.” Many are unaware that water vapor is our most dominant greenhouse gas, and it’s distribution throughout the atmosphere has a multitude of effects on daily weather.

The most perceptible effect of water vapor is on our level of comfort at the surface. Humid days make the air feel heavy and oppressive. That is especially true when air temperatures reach the 80’s and 90’s. At those temperatures, high dew points can add 5, 10, sometimes even 15° or more to the “Feels Like” temperature. Those conditions make the heat more dangerous because the high water vapor prevents the air from being able to evaporate your sweat effectively, which in turn limits your body’s ability to cool itself.

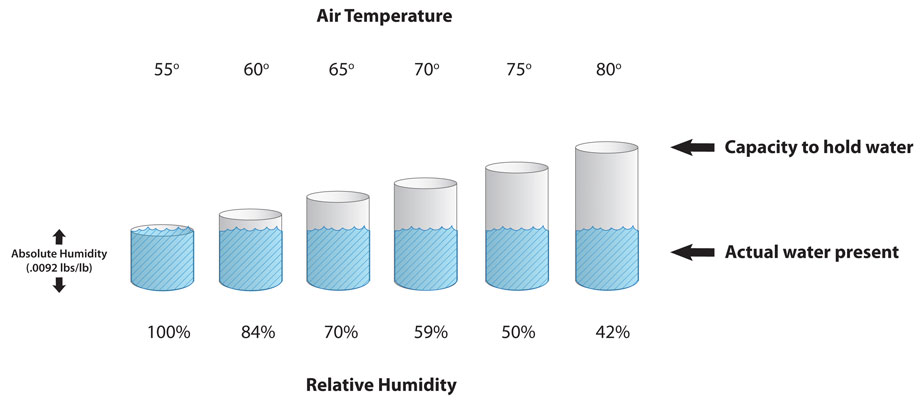

During the summer, we will most often note t he dew point rather than the relative humidity. What is the difference? As noted in this article from the National Weather Service “dew point is the temperature the air needs to be cooled to (at constant pressure) in order to achieve a relative humidity (RH) of 100%.” Relative humidity is deceptive because warmer air expands, so it can hold more vapor than cold air (see image). So, 50% RH will be nearly imperceptible at 30°, will be pleasant at 60°, and will be unpleasant at 90°. However, DP is consistent regardless of air temperature. Dew Points below 55° are generally pleasant, while it becomes sticky in the 55-65° range, and becomes oppressive if it goes over 65°. Dew Point relative to the air temperature also determines the formation of fog and frost.

he dew point rather than the relative humidity. What is the difference? As noted in this article from the National Weather Service “dew point is the temperature the air needs to be cooled to (at constant pressure) in order to achieve a relative humidity (RH) of 100%.” Relative humidity is deceptive because warmer air expands, so it can hold more vapor than cold air (see image). So, 50% RH will be nearly imperceptible at 30°, will be pleasant at 60°, and will be unpleasant at 90°. However, DP is consistent regardless of air temperature. Dew Points below 55° are generally pleasant, while it becomes sticky in the 55-65° range, and becomes oppressive if it goes over 65°. Dew Point relative to the air temperature also determines the formation of fog and frost.

While high dew points raise the “Feels Like” temperature, conversely it can help keep actual air temperatures a bit lower during the heat of the day, while keeping actual temperatures higher at night. That is because the high vapor content works like a sunshine filter during the daytime, and works like an insulator that slows the exchange of heat between the surface and air at night. Prolonged periods of high dew points at night can lead to damage to some crops during their pollination times. By the same token, low DP removes inhibition of heat exchange. Dry air can warm quickly in the sunshine and cool quickly at night. Low DP periods with low cloud cover are often the days where we will see 25-35° spreads between our morning lows and daily highs.

Water vapor content and placement play many more large roles in our weather conditions through all levels of the atmosphere, and we may revisit this when Winter rolls around, and we’ll further explain PWAT when storm season rolls back around, or if we have a heavy rain event before then. But for now, this article covers most of the perceptible effects of water vapor in the form of humidity at the surface. We hope you find this helpful in understanding some of the terminology we use, and the basic mechanics of our perceptible weather.

Micah and Kristen